EXHIBIT OF THE MONTH 2018 |

← |

April

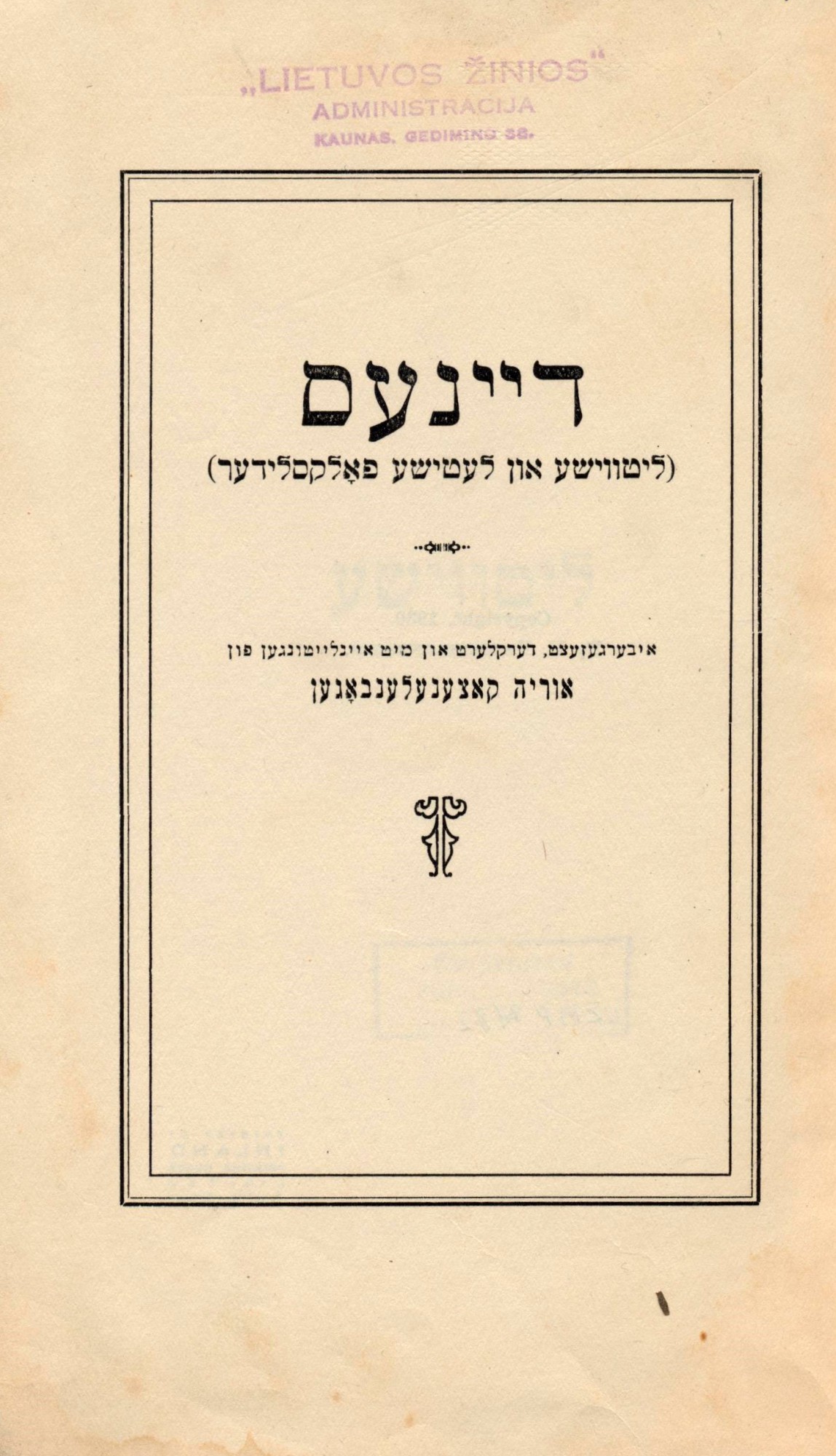

Book "Daines: Litviše un Letiše folkslider" (Songs: Lithuanian and Latvian Folk Songs) in Yiddish, compiled and translated by Urija Kacenelnbogen, Toronto: Inland Printing House Limited, 427 p.; VŽMP 482 |

| The Museum’s holdings include a book in Yiddish published in 1930 in Toronto and titled Daines: Litviše un Letiše folkslider (Songs: Lithuanian and Latvian Folk Songs) as complied and translated into Yiddish, commented and prepared for printing by Urija Kacenelenbogen.  Urija Kacenelenbogen (1885–1980) was a Vilnius-born Jewish writer, publicist, translator, public activist and active promoter of cultural co-existence and close ties between Lithuanian Jews and other nations. In 1904, he published a play Kraft un libe (Power and Love) which became one of the first works of modern Yiddish literature in Vilnius. In 1914, Kacenelenbogen edited the weekly Naš kraj (Our Region) and in 1914–1922 published the Jewish cultural almanac Lite. In 1927, he emigrated for the USA where he taught at various Jewish schools in North America and translated literary texts and publications into Lithuanian, Belarussian and Latvian. Daines – unique compilation of Baltic folklore – was one of his biggest and most significant works. Kacenelenbogen starts his compilation with a foreword where he speaks about the specific nature, themes and peculiarities of Lithuanian and Latvian folk songs, including the translation issues that he encountered along the way and solutions to them. In the compilation the author presents the translation of around 600 Lithuanian and Latvian folk songs (calendar, historical, war, love, family, children, wailing, work, polyphonic, humoristic, wedding songs) into Yiddish, including music sheets of five Lithuanian and five Latvian folk songs. Kacenelenbogen finishes his compilation with a list of reference sources that he used to find the songs that were translated into Yiddish and presents an exhaustive bibliography of Baltic folklore. Prepared by Jovita Stundžiaitė-Olšauskienė, Conservationist and Researcher of Auxiliary Holdings at VGSJM © From the holdings of VGSJM |

May

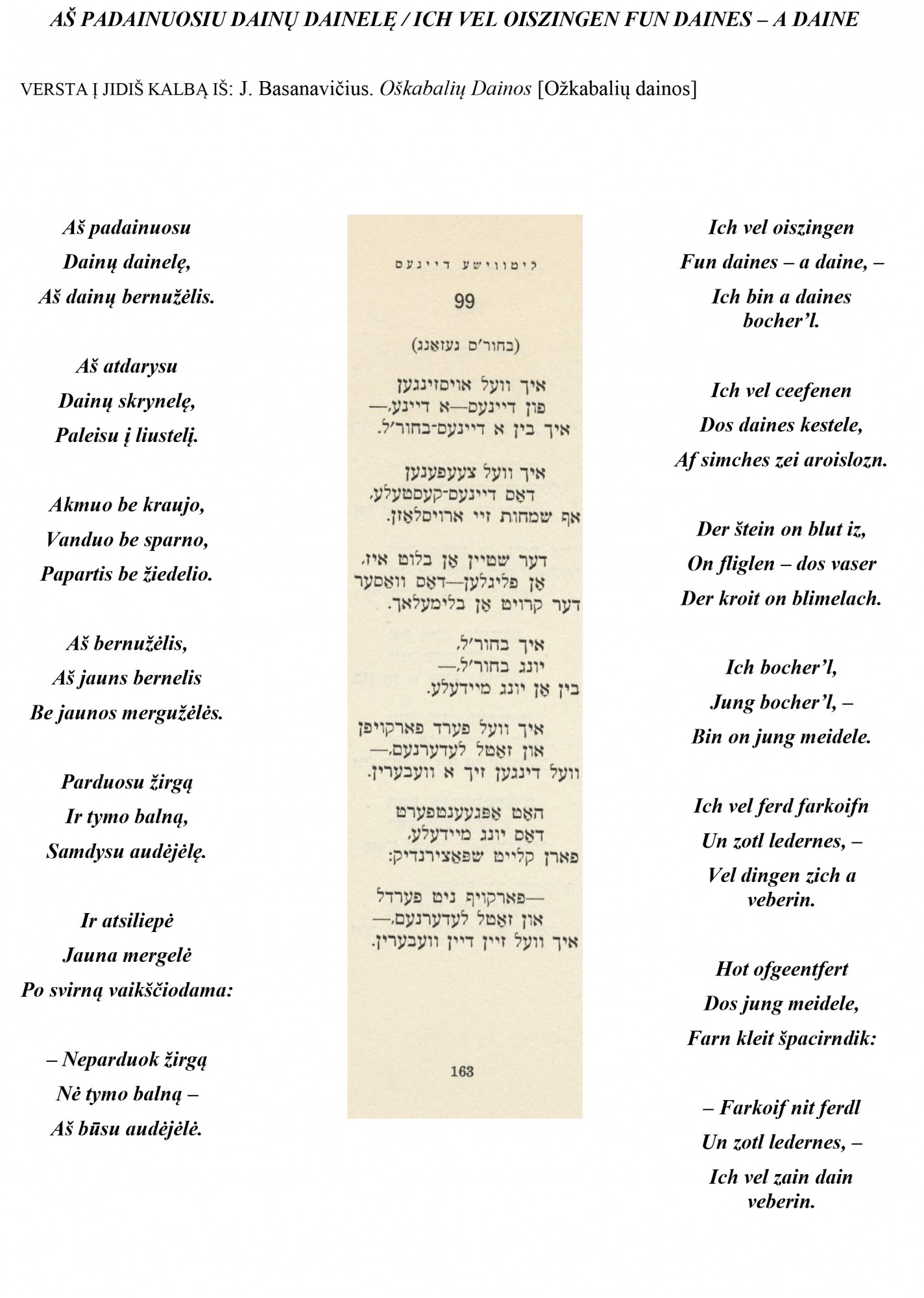

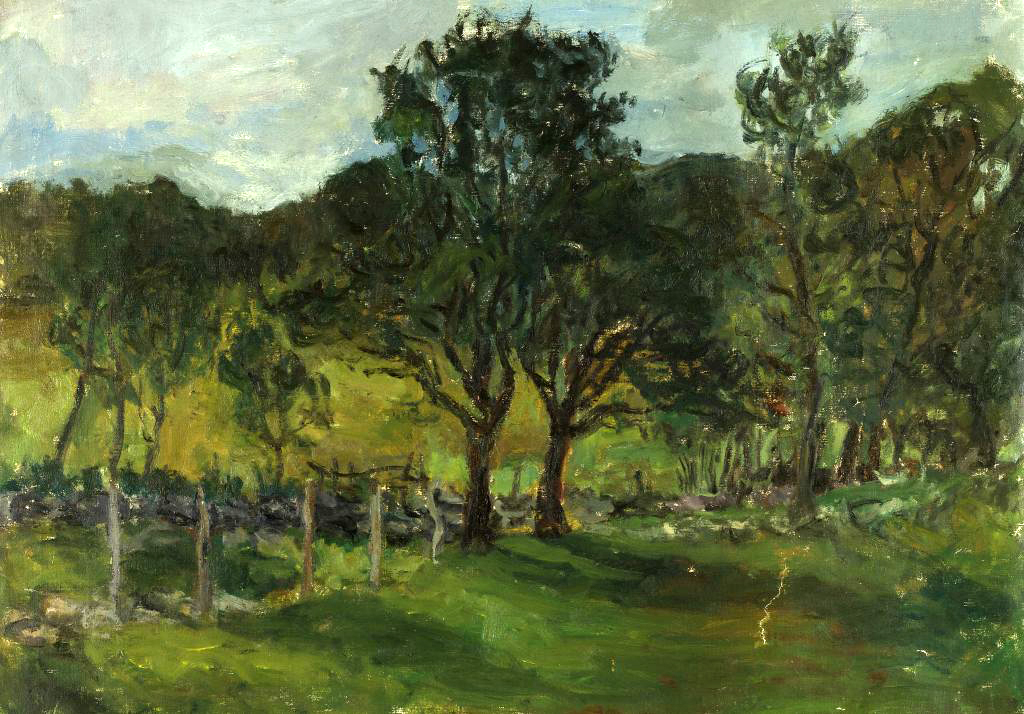

| Neemija Arbit Blatas, Lithuanian Landscape in Summertime Gift by Michael Philip Davis and Albert J. Bird |

| Neemiya Arbit Blatas is one of the most famous expatriate Litvak artists. His vast artistic legacy received numerous medals and other awards, such as the French Order of the Legion of Honour, Golden Order of Honour of the City of Venice, Masada Medal, Order of the President of Italy, Medal of Commander of Arts of the City of Paris, and others. The painter was bestowed the Honorary Citizenship of New York City. Arbit Blatas was born in Kaunas in 1908. He graduated from a Jewish gymnasium and at the age of sixteen left for his art studies in Berlin; later studied in Munich and Dresden. As of 1926, the artist settled down in Paris where he met the most famous representatives of the School of Paris (École de Paris) – Mark Chagall, Chaim Soutine, Jacques Lipchitz, Pinchus Krémègne, Michel Kikoïne and others. World War II broke out when Arbit Blatas was in New York. His mother perished in the Bergen–Belsen concentration camp. His father, who had survived the atrocities of the Dachau concentration camp, died soon after the war. Many years later, the artists visited Lithuania several times: in 1975, 1988 and 1990. Arbit Blatas died in New York in 1999.

When in Paris, Arbit Blatas had never forgotten his homeland. In Lithuania, he held exhibitions, wrote exhibition reviews and published articles for Lithuanian newspapers about the life of Parisian bohemia. In 1932, Arbit Blatas established a Contemporary Art Gallery in Kaunas. When the artist returned to his home country, he would regularly take part in painting sessions in the open air and paint Lithuanian nature. Visitors of art exhibitions held in the interwar period had a chance to admire Lithuanian landscapes painted by Arbit Blatas. The early paintings of Arbit Blatas from the Lithuanian period are extremely scarce. Several works from this period are held in national museums of Lithuania and private collections. Therefore, the six paintings from this early period – five landscapes and a portrait – presented by Michael Philip Davis, a step-son of Artib Blatas, to the Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum make a truly special gift. The landscapes by Arbit Blatas portray meadows and forests painted in multiple shades of green, whereas his sky shimmers in a multitude of bluish grey halftones. This is what the French critic Waldemar George said about the painter’s landscapes in the bulletin L’Intransigent of 1935: ‘Nature painted by Arbit Blatas speaks to us. His works reflect the spirit of his native Lithuania...’ The works of Arbit Blatas donated to the Museum by Michael Philip Davis will stay on display from 6 June to 16 November as part of the exhibition ‘Lithuania in Litvak Arts’ organised at the Tolerance Centre of the Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum (Naugarduko St. 10/2, Vilnius). Written by Dr. Vilma Gradinskaitė |

July

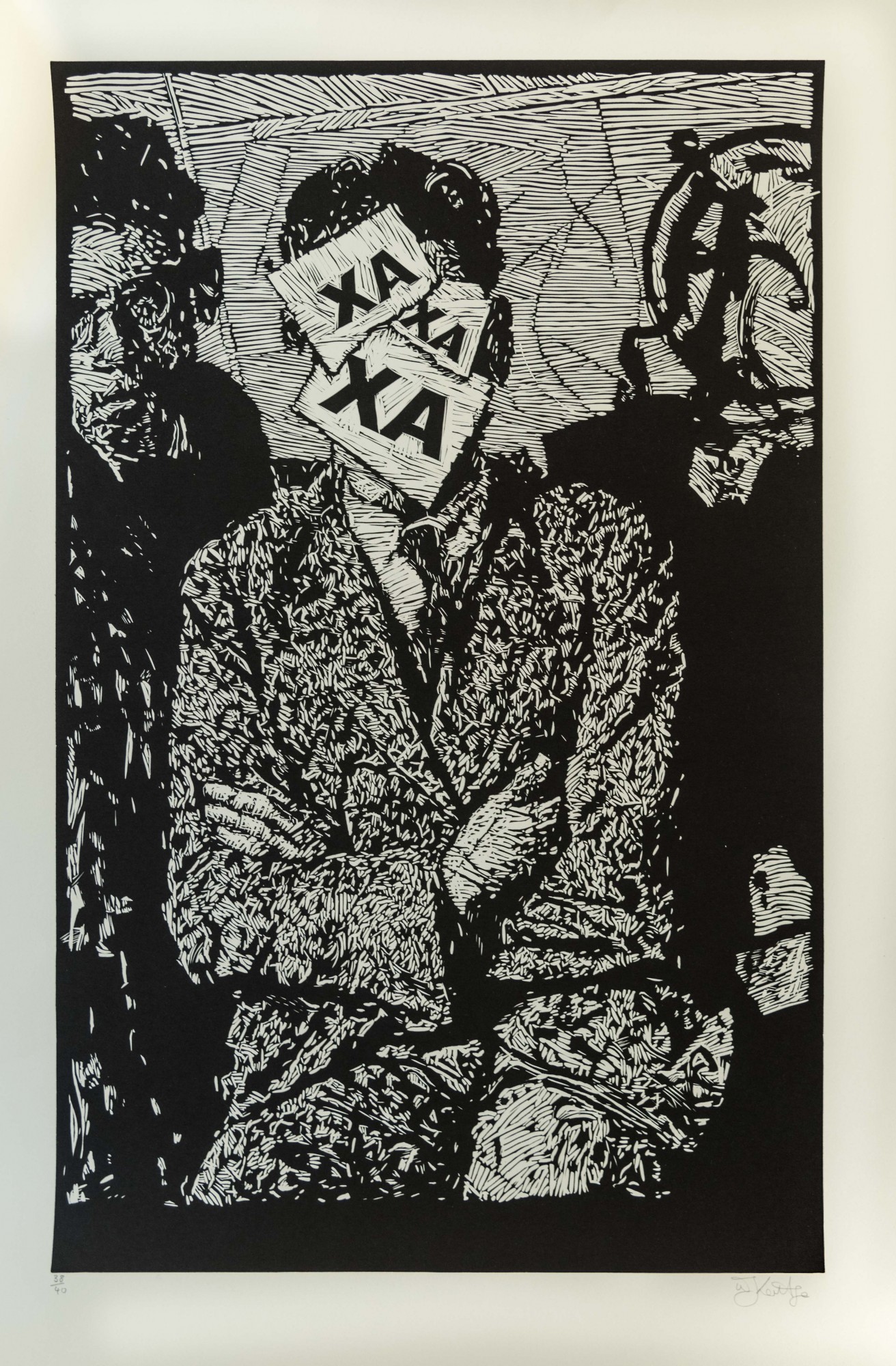

| William Kentridge, XA XA XA, 2010. Linocut, 95 X 57, run 38/40, VGSJM |

| William Kentridge (born in 1955 in Johannesburg, Republic of South Africa), whose grandparents on his father’s side came from Lithuania, is one of the most famous interdisciplinary artists of SAR. He is actively working in multiple artistic fields, such as graphic art, scenography, animation, performance and video art. As the son of two lawyers who fought against the Apartheid regime, he learned to question the imbalance of powers in the country rather early in his life. The artist uses various means of expression to present political events disguised as affecting poetic allegories. Kentridge is especially fond of the animation technique which involves photographs of drawings in charcoal and paper collages with all the changes to the drawings and erasures preserved. Kentridge has already held exhibitions in almost all of the world’s most famous museums. His artwork was presented at Documenta exhibitions X, XI, XIII in Kassel, Germany (1997, 2002, 2012), Sao Paulo Biennial in Brazil (1998), Venice Biennial (1999), Havana Biennial in Cuba (2000), and Sydney Biennial in Australia (2008). Kentridge received numerous invitations to work on opera scenography. His opera and theatre projects were presented at festivals in Grahamstown (South Africa), Avignon (France), Salzburg (Austria) and elsewhere. One of his most famous works was the staging of the opera ‘The Nose’ by Dmitry Shostakovich in 2006. The plot of ‘The Nose’ became a perfect means to its author Nikolay Gogol to speak ironically about Russia in the 1830s – the period of despotism, terror, heavy bureaucracy and social division. Gogol’s story helped Kentridge in his research into the recent history of his own fatherland. Kentridge integrated the absurd and bureaucratic tyranny of Gogol’s Russia with Stalin’s regime and the recent history of Apartheid in South Africa. The linocut that the artist donated to the Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum is dedicated to the crackdown of Stalin’s opponents. The artwork portrays Nikolai Bukharin, a Bolshevik condemned to death, in whose final story laugh and death are intertwined in a macabre way. His political impotence is expressed by covering his lost nose with the words XA XA XA. Prepared by Karina Simonson, Museology Specialist at the History Research Department of the Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum |

August

| Jacques Lipchitz. Drawing for the sculpture The Escape. Toulouse, 1940 Paper, pencil, ink; 33 x 25.4 VGSJM |

| World famous cubist sculptor Jacques Lipchitz (1891–1973) was born in August some 127 years ago in Druskininkai. This August, one of the most famous works by Lipchitz from the Museum’s collection is presented here as the exhibit of the month. In summer 1940, Lipchitz started drawing sketches for his sculpture The Escape which is considered to be his last work from the Paris period before leaving for the USA. The majority of his famous works from this particular period were created in his studio in Paris, in the Forest of Boulogne, which was designed by the sculptor’s friend Le Corbusier. However, The Escape was created in Toulouse, because the moment the Germans entered Paris, the sculptor and his first wife Berta abandoned all their activities in Paris and hastily left for Toulouse leaving a unique collection of works behind, including the studio, which the sculptor entrusted to his friends. Supposedly, the sculpture was inspired by the baroque masterpiece of Gian Lorenzo Bernini Apollo and Daphne. The drawing The Escape portrays two figures – a man and a woman – in desperate movement. The woman’s hands are stretched upward as if begging, with her head drawn to one side in despair or horror. The silhouette of the man firmly holding the woman or supporting the female figure who is leaning against him causes a two-fold impression – that of a saviour and an aggressor. Lipchitz created The Escape as if anticipating the approaching doom. With a passport which was about to expire, the sculptor and his wife had to hastily leave Toulouse for Portugal. From Portugal they took a ship, crammed with people, across the Atlantic to the USA. Lipchitz slipped on a ladder on the ship and almost drowned. This experience haunted the artist who finally reached a safe haven in the USA for many years to come. He created a series of sketches depicting some ideas for his future sculptures, such as The Escape and The Road to Exile. Some sketches depict people carrying other human beings on their back. The escapees may have already reached a safe haven, but the hard road to exile is still ahead of them. Yet other sketches depict a desperately screaming figure carrying a man who is on fire. This is an allusion to the fact that not all of the escapees had safely reached the port of destination. In 2016, the Museum of Jewish Art and History in Paris attributed the sculpture The Escape,which is based on this drawing, to the five most significant exhibits of the museum. Prepared by VGSJM Museology Specialist Aušra Rožankevičiūtė |

September

| Masha Rolnik‘s schoolbag, VŽM7759 |

| Masha Rolnik (Marija Rolnikaitė) was born on 21 July 1927 into the family of Hirsh and Taiba Rolnik (Hiršas Rolnikas and Taiba Rolnikienė), who at that time lived in Klaipėda, but later moved to Plungė. Her father was a lawyer and her mother was a housewife. After some time the family with their four children – Miriam, Masha, Raja and Ruvik – moved to Vilnius. Right after the war broke out, they all tried to retreat to the East, but only Hirsh Rolnik successfully escaped. He spent the rest of the war in the 16th Lithuanian Division. On 6 September 1941, Taiba Rolnik and the children were imprisoned in the Vilna Ghetto. At that time Masha was fourteen years old. There were a dozen thousand children imprisoned in the ghetto, therefore teachers immediately took to establishing schools and taking care of the children’s education and occupation there. At first, due to the extensive mass annihilation of Jews, the schools failed to operate on a regular basis. There were several schools in the Big Ghetto: primary school, secondary school with Yiddish as the language of instruction, and gymnasium. In addition, there were two religious schools and two yeshivas. All of them were located further from the gate of the ghetto to protect children from unexpected raids by the Nazis and the local police aimed at selecting victims for the mass killings in Paneriai. Still, at first the parents avoided registering their children with schools in fear of making it easier for the Nazis to select their children for killings when they get hold of the lists of schoolchildren. In 1943, the schools in the ghetto still operated, but were half empty… Despite her strong wish, Masha was unable to attend a school in the ghetto, because she had to work and take care of her family. Nonetheless, she persistently believed that one day she will be able to continue with her studies and thus preserved her schoolbag throughout her imprisonment in the ghetto. In her memoirs Masha wrote the following: ‘Only during my first year in the ghetto I was still the same person. I was so worried that a new schoolyear was about to start and I was there, unable to go to school. It was so sad when the second schoolyear started without me… ’. In the process of liquidating the Vilna Ghetto, Taiba Rolnik with nine-year-old Raja and seven-year-old Ruvik were taken to the Nazi concentration camp in Auschwitz where they supposedly were killed in a gas camera. Masha was taken to the Nazi forced labour camps in Latvia – first to Kaizervalde, then to Strassdenhof – and finally to the Nazi concentration camp in Stutthof (Germany). Her sister Miriam was saved by Henrikas Jonaitis, a teacher, as assisted by priest Juozas Stakauskas. Hirsh, Masha and Miriam Rolnik survived the Holocaust. After the war they all met in Vilnius. Masha described her experience in her memoirs which were first published in 1963. Her book I Must Tell was translated into 18 languages. We met Masha Rolnik in July 1999 in her home in Saint Petersburg. It was then that she donated some of her personal belongings to the Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum. Her schoolbag was one of them. ‘This is part of my life, part of me, the painful part…,’ she said when handing over the schoolbag to me. Masha Rolnik died on 7 April 2016 in Saint Petersburg. Prepared by Neringa Latvytė-Gustaitienė, Head of History Research Department at VGSJM |

October

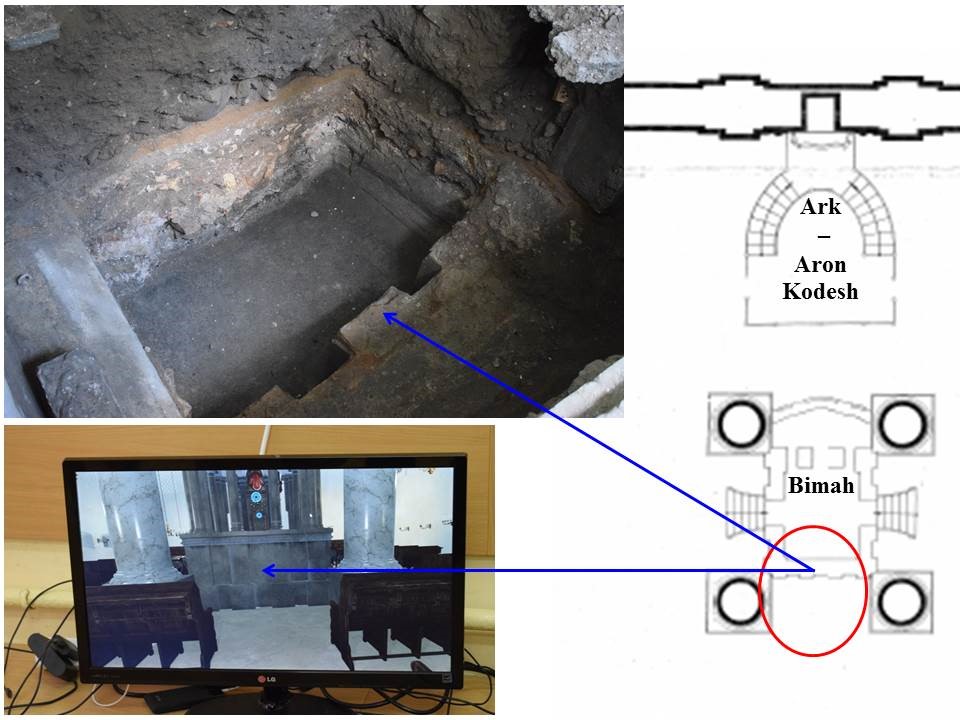

Photograph dating back to around 1945. Inventory No. VŽM 1828-2

Interior of the Great Synagogue of Vilna |

| The Great Synagogue of Vilna is not only an inseparable part of Jewish history but also a part of multinational Vilnius and Lithuania. It is closely connected to Vilna Gaon, the great Jewish thinker who lived and expounded his teachings in Vilnius, which was then the Eastern European centre of Jewish religion, culture and philosophy. One of the key highlights of the time was the Great Synagogue which was surrounded by a group of smaller synagogues and houses of prayer forming a shulhoyf (Yiddish for a synagogue courtyard). The photograph below depicts one of the most important parts of the interior of the Great Synagogue of Vilna – bimah. In the middle of the hall of prayer of the Great Synagogue there was a podium, which was surrounded by four massive supporting pillars, and which was decorated with twelve smaller columns and a decorative dome. The photograph dates back to around 1945 after the end of World War II. In 1955–1957, the remains of the Great Synagogue and the synagogue courtyard – shulhoyf – were finally pulled down and erased from the surface of the earth. In 1964, a brick kindergarten building was erected on the site of the Great Synagogue covering half of the floor area of the synagogue that once stood there. In 2002–2017, it was home to Vytė Nemunėlis Primary School. In 2011, archaeological excavations started on the site of the Great Synagogue, which resulted in the discovery of a number of important elements. In 2011, a fragment of one of the four massive supporting pillars was discovered.  Photgraph No. 1: In 2011, a fragment of one of the four massive supporting pillars was discovered The archaeological research performed on 9–31 July 2018 (headed by Dr Jon Seligman, head of the Excavations, Surveys and Research Department of the Israel Antiquities Authority, and archaeologist Justinas Račas (Public Institution Kultūros paveldo išsaugojimo pajėgos)) revealed that there were still fragments of the bimah of the Great Synagogue of Vilna under the brick kindergarten building.  Photograph No. 2: Dr Jon Seligman shows the remains of the bimah of the Great Synagogue of Vilna to the Mayor of Vilnius Remigijus Šimašius Source: https://www.facebook.com/Vilna.Synagogue.Project/photos/a.205890109750424/711714709167959/?type=3&theater  Photograph No. 3. Scheme of the bimah and the fragment of it discovered at the excavation site The photographs from the archaeological site of the Great Synagogue of Vilna dating back to 2011 and 2018 (Photographs No 1, 2 and 3) are courtesy of The Vilna Great Synagogue and Shulhoyf Research Project Prepared by Olga Movšovič Conservationist-researcher at the Inventory and Conservation of Holdings Department © Image No. VŽM 1828-2 from the VGSJM collection |

December

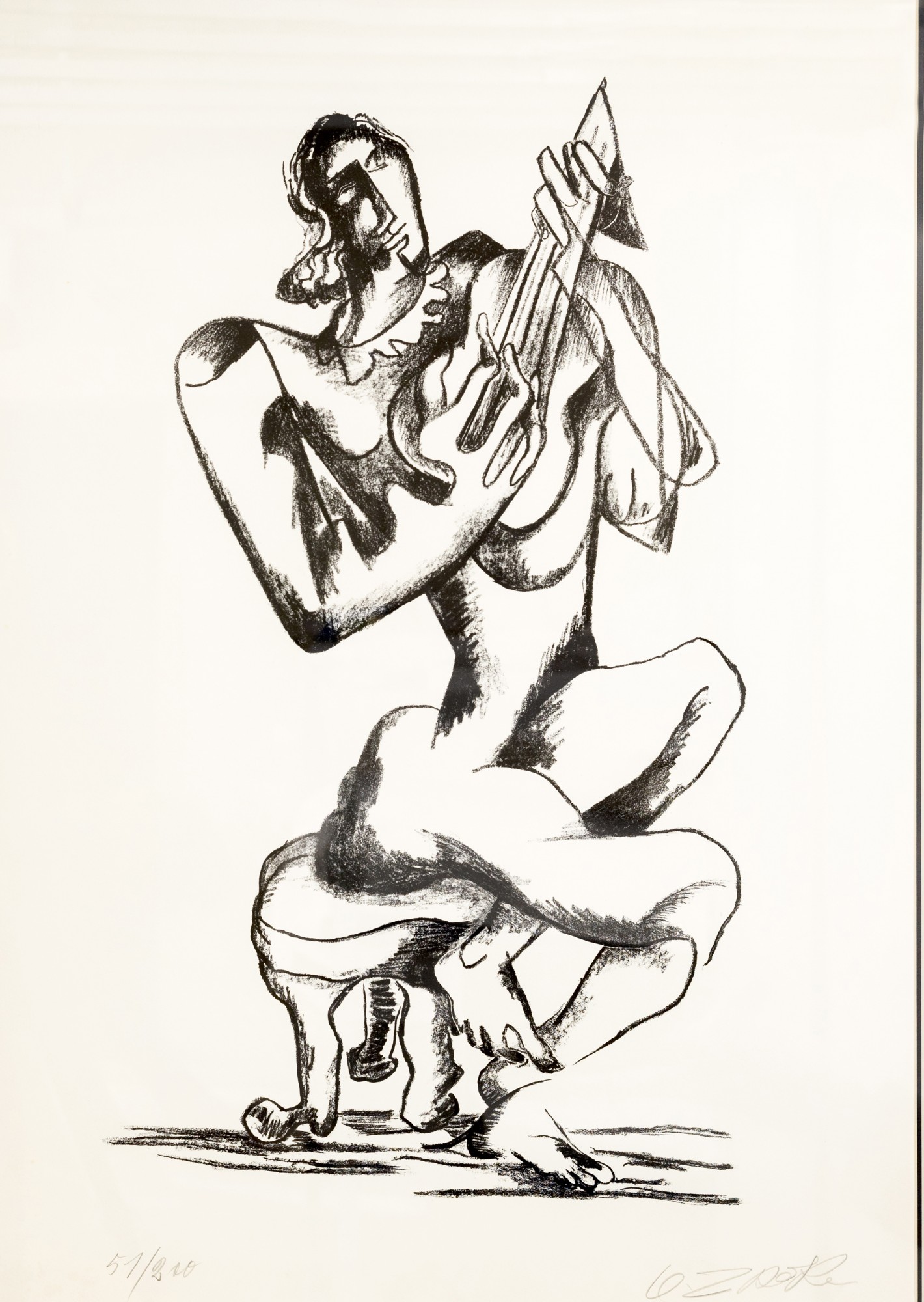

| Ossip Zadkine.Man Playing the Lute. Paper, lithography. 1920s |

| Ossip Zadkine – sculptor, graphic artist, poet – was born in 1888 in Vitebsk (other sources say that he was born in Smolensk) into the family of a Scottish mother and a Jewish father. He attended Yehuda Pen’s School of Drawing in Vitebsk together with Marc Chagall and Lazar Lisickij. In 1907, encouraged by his family, Zadkine left for London to study. In 1909, he went to Paris where he attended the National School of Arts for a short time before being accepted into the famous La Ruche. The sculptor contributed to the establishment of Cubism as a new trend in art. He offered accommodation to his friends from Vitebsk Marc Chagall and Lazar Lisickij and introduced them to the Parisian artists Amedeo Modigliani, Chaim Soutine and Henri Leger. In 1915, during World War I, Ossip Zadkine served as a volunteer in a military hospital. After the war, he took part in many exhibitions in Europe. He soon won wide recognition. Zadkine’s works dating back to the 1920s are his contribution to Cubism and music. His collection of musicians, composers, accordionists and violinists is based on the cubist idea of recreating a human figure in geometrised forms. His works of the time represent melody cast in bronze, painted on canvas and imprinted on paper. Zadkine spent World War II in the USA. When the war was over, he returned to Paris. It was then that he created a number of works on the pacifist theme. In 1953, his sculpture The Destroyed City was unveiled in Rotterdam. It is his most prominent work. Zadkine held around 150 solo exhibitions of sculpture and graphic art throughout Europe, Great Britain and the USA during this post-war period. Even though Zadkine’s works underwent major transformation starting with Cubism and going on to Expressionism throughout the 20th century, he preserved his individual plastic manner and his inimitable touch. The principle of contra-relief has always dominated his works. The space in his artwork seems to be turned inside out. Zadkine’s works can be found in many museums throughout the world. The Zadkine Museum in Paris, which opened in 1982, boasts the biggest collection of his artwork. The Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum’s collection contains a graphic work by Ossip Zadkine Man Playing the Lute which dates from the 1920s. In the lithograph the author combines features of Cubism and Primitivism, and employs embossed and arched planes, including flowing baroque forms. Prepared by Irina Nikitina, conservationist-researcher of holdings at the Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum Photograph by Paulius Račiūnas © Photograph courtesy of the VGSJM collection |

| ↑ | ← |