EXHIBIT OF THE MONTH 2020 |

← |

January

SHELTER, 1959 (oil on canvas)

| In the 1950s, Bak thought that the horror he had experienced in the Holocaust could be expressed by abstract means. |

| Following his graduation from École des Beaux Arts in Paris, Bak started painting intensely. In 1959, Bak went to Rome, where his first exhibition of abstract paintings enjoyed great success. In 1961, he presented his works at the International Carnegie Exhibition in Pittsburgh. In 1963, he had solo exhibitions in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. Bak had now earned international recognition. In the 1950s, abstract expressionism (born in the 1940s in the community of New York artists) became one of the hottest art trends. At that time Bak thought that it is best to convey all the horror which he had experienced during the Holocaust by abstract means and arte povera style. He made collages: he glued wool soaked in water and black or white paper on canvas thus building texture, he used what could be found in nature – dirt and soil. Shelter is a recollection of what Bak experienced when he was hiding from raids with his mother in the bomb shelter: something is burning, there is noise, bombs are falling, only stones, lime, dirt, and abyss remain. “I must confess to one thing: I painted in Rome in accordance with what was valid at the time. The abstract form helped to avoid details, which are too painful, and to maintain distance between me and them,” Bak said. Samuel Bak was born in 1933 in Vilnius. At the age of nine, Bak staged his first exhibition at the Vilna Ghetto. By the end of WWII, Samuel and his mother were the only members of his extensive family to survive. They were living in the displaced persons camp in Landsberg, Germany. Subsequently, the artist lived in Israel, Italy, France, and Switzerland before finally settling in the United States of America, where he continues his creative path. Prepared by Ieva Šadzevičienė, Head of VGSJM Tolerance Center and Samuel Bak Museum. |

Februrary

| Irving Norman, Golden Calf, 1957, oil on canvas, 211x140 cm |

| In 2008, the Museum received a gift – the Colden Calf, a painting by Irving Norman, donated by the artist's wife Hela Norman and art patron Susan Carson. IrvingNorman was born Isaac Noachovich on 10 January 1906 in Vilnius, which at that time was part of the Russian Empire (died in 1989 in Gales Ferry, Connecticut). His father Yehuda Leiba Noachovich and his mother Nachame were shopkeepers. Irving was nine when the Germans took over the city in 1915. At the same time his father abandoned the family, but his mother found the strength to raise her four children – a daughter Betty and three sons Irving, Henry and Albert – alone. Irving loved drawing from early childhood. His first drawings depicted the city of Vilnius occupied by the German army. The family lived in poverty and Irving did his best to help his mother provide for it. He sold newspapers on the streets and decorated the windows of his mother’s shop with advertising that he drew himself to attract customers. Irving remembered: ‘My uncle considered me to be a promising artist, he even wanted me to go to art school, but then the war broke out and all the plans were ruined.’ After Poland occupied Vilnius, the family moved to Kaunas. This is what Norman remembered about this period of his life: ‘I was selling newspapers. I had the biggest number of buyers in the whole city and was both free and, to tell the truth, absolutely happy.’ In 1923, 17-year-old Irving emigrated to the USA with his sister Betty. Later the artist remembered: ‘We had a dream… we were dreaming about this country. We developed a special interest in it as a result of the American movies that we watched at the time we lived in Kaunas. American movies, metropolis, and people driving cars. I used to say: God, if people can afford to drive cars, I bet they have enough bread to eat, too.’ Norman settled down in New York and found a job as a barber. In 1925, his mother and brothers Henry and Albert arrived from Lithuania, too. In 1929, Norman became a US citizen. In 1938, he joined the army as a volunteer to fight Fascism in Spain. According to Norman, it was a war between democracy and Fascism, a war between good and evil, and he absolutely had to take part in it. The fight between good and evil continued throughout the artist’s life and later continued in his paintings. Russian poet and artist Boris Pasternak once said the following: ‘Every generation has its own fool who keeps telling the truth the way he sees it.’ Norman devoted his creative life to truth. In his large-scale paintings in the style of social surrealism the painter rebelled against consumerism and collective greed, religious fanaticism and political corruption in the world. His monumental, politicised art full of symbols annoyed the US art elite for many years. In 1950, his watercolour Megapolis,dated 1949 was even removed from an exhibition in San Francisco. It was the only painting ever removed from the museum. It was only in 1970 that Norman’s artwork received recognition. In 1973, art critic Alfred Frankenstein wrote: ‘Until now were unable to understand Irving Norman. For a long time his paintings seemed to be too large for us… too detailed… overly critical of the American society.’ Norman’s artwork could be said to be a chronicle of our times. The Golden Calf is part of the chronicle, too. In his work the painter reminds us of the Israelite story of worshiping a golden calf (ST, Exodus 24:12–18, 32:1–30) and reflects on it through the prism of life in a modern megapolis. The far background of the painting is reminiscent of the Decalogue tablet that Moses brought down from Mount Sinai with the initial words of all Ten Commandments inscribed in two columns. Unfortunately, busy residents of the megapolis do not care about the norms of ethics and morale anymore. Nowadays this message of the painter is as topical as ever. Dr Vilma Gradinskaitė, museology specialist at the History Research Department of VGSJM. |

March

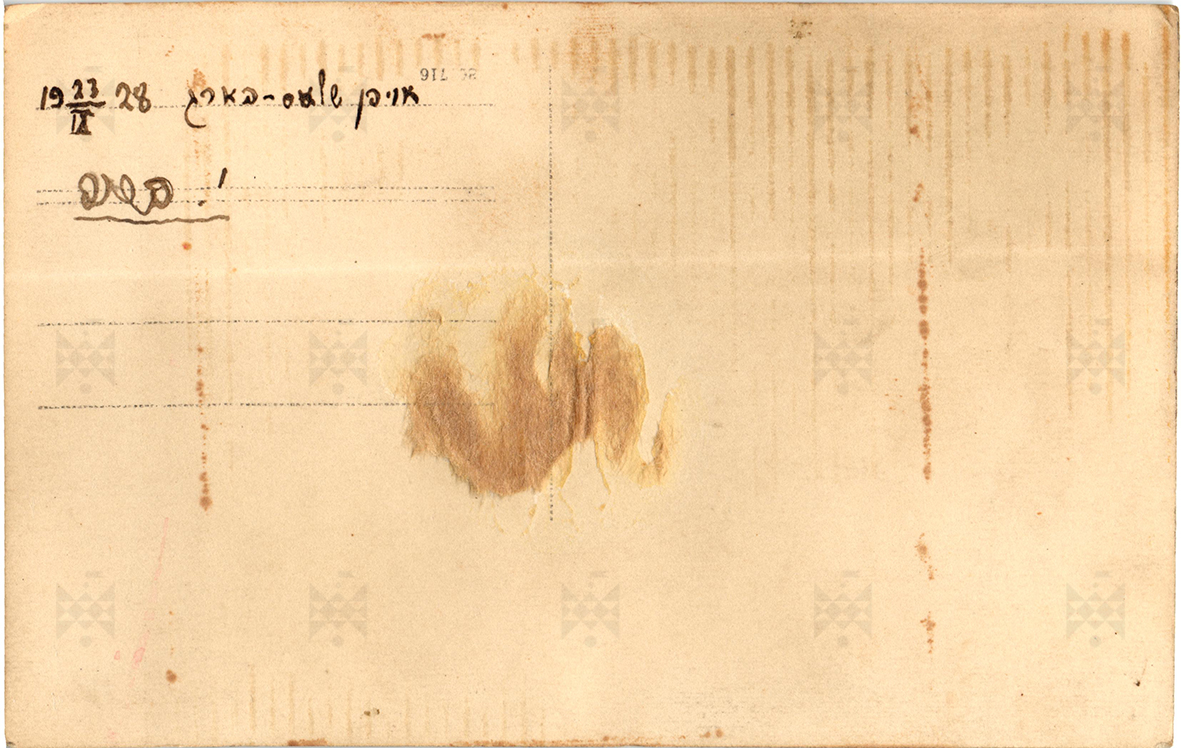

| The digital photograph (inventory No. VŽMP 8293/ 61) is a present to the Museum from Zyron Krupenia from Australia after his visit to the Tolerance Centre in Vilnius in 2019. His father Israel Krup, was born in Vilnius and lived here till 1930 before later emigrating to South Africa. On the reverse side of the photograph there is an inscription in Hebrew made in black pencil, which reads: אוּיפן שלאַס - בארג / 1928.9.23 / י. קרופ. (On Castle Hill, 23/09/1928 I. Krup [Izraelis Krupenia]) |

| It is a group portrait of six young Jewish men posing next to a cross decorated with wreaths on Castle Hill in Vilnius (this was the name of Gediminas Hill according to the Polish tradition). The posed group portrait was made in September 1928. Oak wreaths hang from the cross and a second wreath made of flowers and greenery leans against the cross. A Polish sign – a cross in an oval frame with an eagle from the Polish coat of arms in the centre and the date 1918.XII.31 – can be seen below the oak wreath (at the end of December 1918, after the German occupation army retreated from Vilnius, the city was controlled for several days by Polish nationalists who referred to themselves as the Vilnius Volunteer Self-Defence Squads).  The cross, which bears the symbols of an anchor and a heart, was designed by architect Antanas Vivulskis (1877–1919) and erected on Gediminas Hill on 17 August 1917 in memory of the priest Fr Stanislovas Išora and Zigmantas Sierakauskas (1826–1863). On that same day the cross was demolished by the German occupation army and was rebuilt on 20 January 1921 to commemorate the anniversary of the uprising. In 1925, two plaques were erected on the site of the cross: one bearing an inscription in Polish saying ‘To the Unknown Soldier’ and the other bearing the names of the participants of the 1863–1864 uprising who were sentenced to death in Lukiškės Square. In June 1940 (yet other sources refer to the beginning of World War II) the cross disappeared again. According to historian Darius Staliūnas (Own or Alien Heritage?: the 1863–1864 Uprising as a Lithuanian Memory Site. – Vilnius, [2008], p. 65), the cross did not disappear during the war, but was allegedly demolished by Lithuanians in 1940. The remains of Zigmantas Sierakauskas and Konstantinas Kalinauskas, leaders of the 1863–1864 uprising, and those of 18 other participants of the then events, were discovered during the excavations performed on Gediminas Hill in 2017–2018. On 22 November 2019, an official reburial ceremony was held, and the remains were moved to another place for eternal rest – the columbarium of the central chapel in Rasos Cemetery in Vilnius. Sources: Vilnius Castle State Cultural Reserve (http://www.vilniauspilys.lt/kulturos-vertybes/); access via Internet: http://www.wilnoteka.lt/artykul/historia-baszty-giedymina-na-wystawie-w-bibliotece-uniwersytetu-wilenskiego, http://mylimasvilnius.lt/2010/12/27/ats-nezinomo-kareivio-kapas-gedimino-kalne Prepared by Jovita Stundžiaitė-Olšauskienė, conservationist-researcher of auxiliary holdings. © VGSJM holdings |

| ↑ | ← |