Exhibit of the month |

← |

Published: 2022-08-31

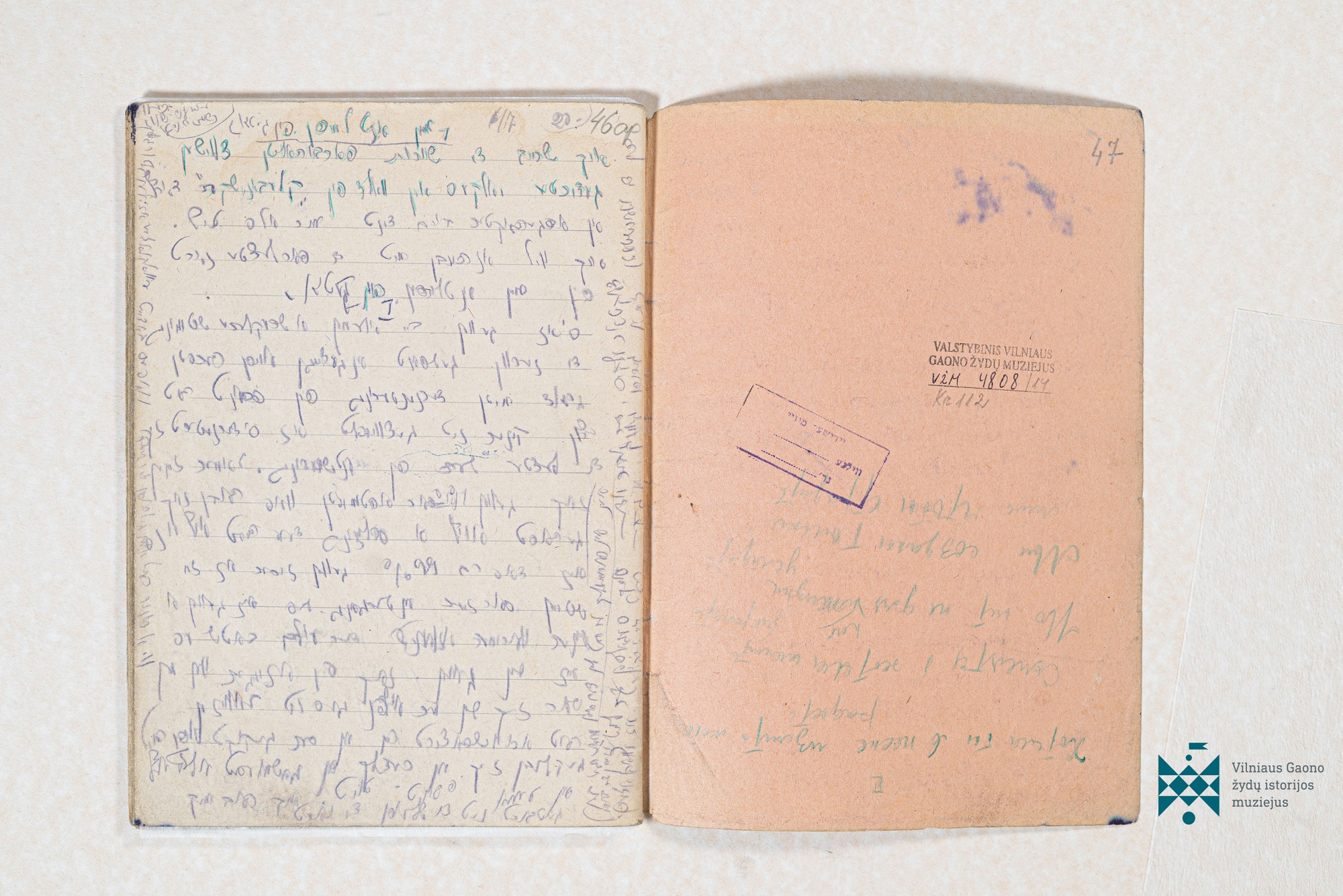

DIARY OF RIVA GAVRONSKA, YIDDISH, MANUSCRIPT, ACC. NO. VŽM 4808

The exhibition presenting the September exhibit is dedicated to honouring and remembering Lithuanian Jews who perished during the Holocaust

First page of the first notebook of Riva Gavronska's diary, manuscript in Yiddish, 1944

Riva Gavronska's hand-written diary is written in Yiddish with a purple or graphite pencil and consists of two small-format semi-thick notebooks. The covers of both notebooks include an indication of the name of the author: Riva Gavronska. The cover of the first notebook contains the date ‘6/VII–1944’, the second – ‘14/VII–1944’. The last line of the handwritten text on the cover of the second notebook shows the name of the author in purple pencil: ‘Rivka Gavronska’.

The exact title of the diary, which is also supported by its content, is ‘My Escape from the Ghetto’. The first sentence of the diary reveals that Riva is writing it after managing to escape from the liquidated Kovno Ghetto: ‘20 July 1944. I write these lines hiding between two pine trees in the forest of Kleboniškiai village. A sprawling tree serves as my table. I want to [tell you] about the last days of my escape’. The specific date given before the first sentence indicates the day the diary was written rather than the date of the events being described. The first excerpt of the diary tells about the historical circumstances of the final days of the Kovno Ghetto, including the desperate efforts of the inmates of the ghetto who had survived to that day to escape from it by all possible means, because the front was approaching, and concentration camps or death awaited them them.

The diary of Riva Gavronska testifies to the vitality of the character of its author, her ability to break out of the clutches of death, confirms in itself that this prisoner of the Kovno Ghetto survived the Catastrophe. However, at this point further study of her life did not give a clearer answer to the question of how her life unfolded after the war. So far, all attempts to trace her name in the already world-famous diaries of the Kovno Ghetto (by Avraham Tory and other prisoners of the ghetto) have failed. Genealogical data in the virtual space points to several individuals bearing Gavronska's maiden name who come from Lithuania, but none of them can be clearly associated with the Riva of these diaries as the existing data is not sufficient.

The following are several fragments of Riva Gavronska's diary translated into Lithuanian and not yet published anywhere.

4 July 1944

Everyone was in a bad mood. Everyone’s nerves were stretched to breaking point. No one doubted that the front was approaching, that our time was almost over, and the decisive moment was approaching. And then another piece of news struck like lightning: Gecke, the commandant of the ghetto, summoned [Moshe] Segalson, the head of the so-called [great] workshops, and the Oberjude [the head of the Jewish Council] and explained to them that as the front was approaching, evacuation of the ghetto was inevitable. He also talked about the swiftly planned evacuation of the entire block. With pale faces and their heads down, the Jews left Gecke's office. The news of the great ordeal immediately spread throughout the ghetto. Everybody more than understood what the evacuation meant for Jews. If one percent of the inmates were optimistic, hoping that a messiah would appear at the last minute, and there would be a miracle, ninety nine percent of the inmates had no doubt that we were on the brink of destruction.

6 July 1944

[...] So I will go to one acquaintance who said he had a good malina and, if there was a need, I could make use of it. If it doesn’t work, then we will try to swim across the river. [...] My brotherthought this was a ridiculous idea: ‘You will not be able to cross the barrage. And you will not be able to swim across the water. Either you will drown in that water, or you'll be shot. I won't go. What ever happens to all Jews will happen to me too. It's too late to be saved...’ ‘Better late than never,’ and having looked around the room I went out. I then went into the second room to Aunt Polia and asked her to attach a star to my back with a pin in case I needed to remove it easily. Being more than sure that I would come back, I did not say goodbye to anyone, just took my bundle with a swimsuit and left.

[...] I looked around. Nothing. I kept on walking. As I approached the cemetery near the beach, I saw a creepy scene that imprinted itself deep into my memory. There were sixteen corpses laying on the ground. All lined up in one row. Night and day victims. They were wrapped in thick white sheets, some completely covered. Some half-covered, only barefoot stiffened legs were visible. There were people gathered there. Some Jews were digging graves. A couple of women brought canvases and wrapped the corpses in them right there on the spot. [...] People were sobbing. And weeping. This was nothing like ‘mourning the deceased.’ This was about the living dead bemoaning the soul of our nation's bitter and cruel fate. People were mourning their relatives who had perished, a small handful of the remaining European Jews (the Kovno Ghetto was the last one in all the Baltic states).

Depressed, with a broken heart and eyes full of tears, I continued on and slowly turned towards the river. I was very surprised to find no one there. Not a living soul. Not even a guard. I couldn't believe my eyes.

I looked around, I kept walking, indeed – no one at all. ‘It's my sky,’ I thought. – ‘Take a chance, because later it may be too late...’ And without thinking any further, I quickly took off my clothes. My fingers were trembling as I put on my swimsuit over my underwear. I stepped into the water, leaving my coat and my dress on the river bank. I looked around again and made sure there was no one around. [...] I started swimming. I swam across and kept looking at the booth next to the sawmill, where a guard with a gun stood. Either he did not notice me or pretended that he did not see me, but he did not move from his spot. Not long before reaching the other bank, I suddenly felt as if I was being dragged down to the bottom. My clothes were soaked with water and it was getting hard to move. I wanted to stand on my feet and rest a while, only it was deep there, and I couldn’t touch the bottom with my feet. Then I threw myself forward, pushed off, and so I rested. Then I swam quickly towards the bank. There were several Lithuanian men standing there. All in swimsuits. Some women were swimmng further away...

[...] The first day of freedom...

Prepared and translated from Yiddish into Lithuanian by Ilona Murauskaitė, curator and researcher of written holdings at VGMJH

© Photograph courtesy of Paulius Račiūnas

© From the holdings of VGMJH

| ↑ | ← |